| Hecl and Java ME | ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

Hecl is designed to be small enough to run on mobile devices such as cell phones. This means that for the Hecl core, has been necessary to limit ourselves to Java API's that work with J2ME.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

This is a tutorial showing you how to use Hecl to write applications for Java ME. If you want a simple introduction to the Hecl language, you can find that here: tutorial. |

This tutorial first appeared here: Create a simple application with Hecl - Introducing Hecl, a mobile phone scripting language . It is a tutorial style introduction writing Hecl code for mobile phones, by David Welton.

The aim of this tutorial is to help you create cell phone applications, so let's get started right away. You'll need a few things first:

Sun's Java. With Ubuntu, you can get this like so:

apt-get install openjdk-6-jdk

Sun's WTK toolkit. While you don't need the tools to compile Hecl (unless you want to hack on it!), you do want the emulator, so that you don't have to load your app onto your phone each time you want to test it. It's not open source software (yet?), but it does run on Linux, Mac and Windows, and of course it is free.

Hecl itself. You can get the latest code here: http://www.hecl.org/downloads/hecl-latest.tgz.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

Hecl is always improving, so you should also consider checking out Hecl directly

from git: |

Sun's WTK requires installation - you can put it somewhere like /opt,

so it won't get mixed up with the rest of your system. The installation process is very

simple - just say yes to a few questions, and you're done. Hecl doesn't require

installation: everything you need is already there in the distribution.

To see if everything's working, you can try launching the emulator with the sample

application: /opt/WTK2.5.2/bin/emulator -classpath

jars/cldc1.1-midp2.0/Hecl.jar Hecl

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

With version 3 of the Sun WTK (which as of 2010-01 only runs

on Windows and Mac), the command line you need is as

follows:

|

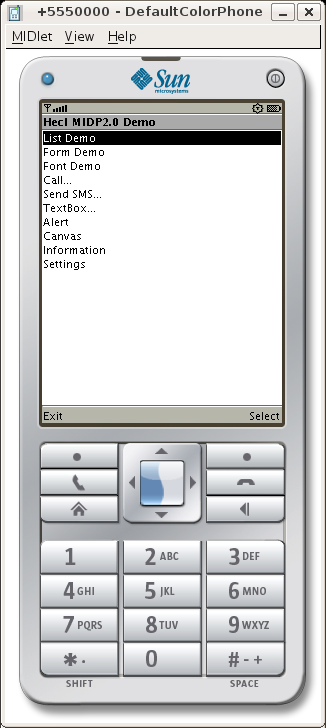

That should bring up something like this:

Figure 1: Hecl demo screen shot

This is Hecl's built in demo - its source code is located in

midp20/script.hcl, but before I get too far ahead of myself, let's go

back and create the classic "Hello World" application, just to get started and see how to

work with Hecl.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

Hecl actually comes in several flavors, with slightly different GUI commands - MIDP1.0 (older phones), which has fewer commands and doesn't do as much, and MIDP2.0, for newer phones, which has a lot more features. This tutorial utilizes the MIDP2.0 commands, because that's what current phones are based on. The concepts described are very similar for the MIDP1.0 commands, but the commands are slightly different. Please contact us if you are interested in a MIDP1.0 version of this tutorial. |

To write your first Hecl program, open a text editor, and type the following program into a

file - I'll call it hello.hcl:

proc HelloEvents {cmd form} {

[lcdui.alert -text "Hellllllllooooo, world!" -timeout forever] setcurrent

}

set form [lcdui.form -title "Hello world" -commandaction HelloEvents]

set cmd [lcdui.command -label "Hello" -longlabel "Hello Command" -type screen]

$form setcurrent

$form addcommand $cmd

$form append [lcdui.stringitem -label "Hello" -text "World"]

Not bad - 8 lines of code, and most of it's pretty clear just from looking at it. I'll go through it line by line, so you understand exactly what's happening.

The first bit of code, that starts with proc HelloEvents, defines a

"procedure": in other words a function called HelloEvents. When this

function is called, it creates an "alert" - think of it as a pop up message telling you

something important. -timeout forever tells the message to stay on the

screen until the user dismisses it.

The second command defines a form, with the command lcdui.form, with

the title of "Hello World", and connected to the HelloEvents

proc. What this connection means is that when any commands associated with the form are

activated by the user, this procedure is called to handle them. The code set

form stores the form object in the variable form, so that it

can be referenced later.

The following line creates a command that can be activated by the user. It has the label

"Hello", and is stored in the variable cmd. I use the

screen type for the command, which is used for user defined

commands. There are some other predefined types such as exit and

back.

$form setcurrent references the previously created form, and tells Hecl to

display it on the screen.

The addcommand subcommand (you could also think of it as a "method", like in an object oriented language) attaches the command I created above to the form. This makes the command visible in the form.

Finally, I display a string on the form with the lcdui.stringitem

command. On most phones, the -label text is displayed in bold, and the

-text text is displayed next to it.

That's it! Now, to transform the code into a cell phone application, run a command:

java -jar jars/JarHack.jar -hecljar jars/cldc1.1-midp2.0/Hecl.jar \

-destdir ~/ -name Hello -script hello.hcl

This is all it takes - this command takes the existing Hecl.jar file,

and replaces the Hecl script within with our newly created hello.hcl

script, and creates the resulting Hello.jar in your home directory

(referenced as ~/ in the command above).

Now, we can run the code in the emulator to see the application:

/opt/WTK2.5.2/bin/emulator -cp ~/Hello.jar Hecl

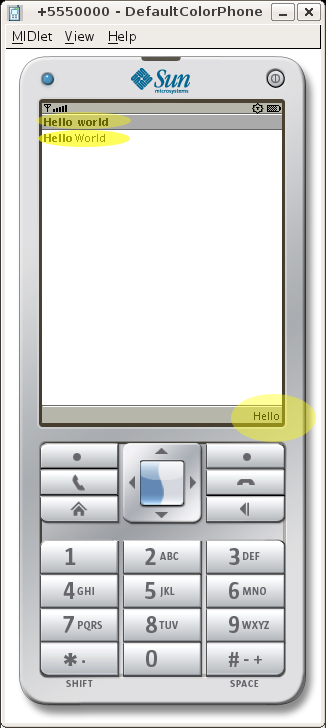

Figure 2: Hecl Hello World screenshot

Highlighted, from the top, are the form's -title, the

stringitem, and in the lower right corner, the command labeled Hello.

If you press the "hello" button, the code in HelloEvents is executed, and an "alert" is popped up onto the screen, and stays there until you hit the "Done" button.

While creating an application is very easy, unfortunately, installing it on a phone is not; there isn't much that Hecl can do to ease that process, which is different for each phone. On Linux, for my Nokia telephone, I use the gammu program to transfer programs to my phone, like so:

gammu nothing --nokiaaddfile Application Hecl

Another method that may work better across different phones is to use the phone's browser to

download and install the application, by placing the .jar and

.jad files on a publicly accessible web server, and accessing the

.jad file.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

|

Note that this will likely cost money in connection charges! |

So far so good. Next, I'll create a small application that you can interact with to do something useful. It's a simplified version of the shopping list that can be found here. The theory of operation behind this application is simple: typing a shopping list into a mobile phone is pretty painful - it's much better to do the data entry via a web page, and then fetch the list with the mobile phone application.

For this tutorial, I've created a simple list on the ShopList web site, with the PIN number

346764, which can be viewed here. Feel free to create your

own shopping lists - the site costs nothing to use. The cell phone application works like

so: by entering the PIN, it downloads the list of items and displays them on the phone

screen as a series of checkboxes. Have a look at the code to do this:

# Process events associated with the shopping list screen.

proc ShopListEvents {exitcmd backcmd cmd shoplist} {

if { eq $cmd $exitcmd } {

midlet.exit

} elseif { eq $cmd $backcmd } {

global shopform

$shopform setcurrent

}

}

# Create a new shopping list screen and fetch .

proc MakeList {exitcmd backcmd pin} {

set url "http://shoplist.dedasys.com/list/fetch/${pin}"

# Fetch the data, and retrieve the data field from the results hash.

set data [hget [http.geturl $url] data]

if { eq $data "PIN NOT FOUND" } {

[lcdui.alert -type warning \

-title "Pin Not Found" \

-timeout forever\

-text "The PIN $pin was not found on shoplist.dedasys.com"] setcurrent

return

}

set shoplist [lcdui.list -title "Shopping List" \

-type multiple]

foreach e [split $data \n] {

$shoplist append $e

}

$shoplist addcommand $exitcmd

$shoplist addcommand $backcmd

$shoplist setcurrent

$shoplist configure -commandaction \

[list ShopListEvents $exitcmd $backcmd]

}

# Process events associated with the main form.

proc ShopFormEvents {backcmd exitcmd pinfield

fetchcmd cmd shopform} {

if { eq $cmd $exitcmd } {

midlet.exit

} elseif { eq $fetchcmd $cmd } {

MakeList $exitcmd $backcmd \

[$pinfield cget -text]

}

}

# The action starts here...

# Create a generic back command.

set backcmd [lcdui.command \

-label Back \

-longlabel Back -type back -priority 1]

# Create an exit command.

set exitcmd [lcdui.command \

-label Exit \

-longlabel Exit -type exit -priority 2]

# Create the form.

set shopform [lcdui.form -title "Shopping List"]

set pinfield [lcdui.textfield \

-label "shoplist.dedasys.com PIN:" \

-type numeric]

set fetchcmd [lcdui.command -label "Fetch" \

-longlabel "Fetch Shopping List" \

-type screen -priority 1]

$shopform append $pinfield

$shopform addcommand $exitcmd

$shopform addcommand $fetchcmd

$shopform setcurrent

$shopform configure -commandaction \

[list ShopFormEvents $backcmd $exitcmd $pinfield $fetchcmd]

This is certainly more complex than the first example, but the general pattern is the same - screen widgets and items are created, displayed, and procs are called to deal with commands.

As I mentioned previously, commands with specific, predefined tasks have their own types, as I can see with the back and exit commands, which are respectively of types "back" and "exit".

After the two commands are defined, I create a form and add a textfield to it. By specifying

-type numeric for the textfield, I indicate that it is only to accept

numbers - no letters or symbols.

After creating the Fetch command, I append the textfield to the form (or else it wouldn't be visible), add the two commands to the form, and then, with setcurrent, make the form visible. The last line of code configures the form to utilize the ShopFormEvents proc to handle events. The list argument warrants further explanation:

Hecl, like many programming languages, has a global command that could be

used in the various procs that utilize the back and

exit commands - you could simply say global backcmd, and

then the $backcmd variable would be available in that procedure. However,

using global variables all over the place gets kind of messy, so what I want to do is pass

in everything that the proc might need, and I do so by creating a list: ShopFormEvents

$backcmd $exitcmd $pinfield $fetchcmd. You can see that these corresponds to the

arguments that the proc takes: proc ShopFormEvents {backcmd exitcmd pinfield fetchcmd

cmd shopform}, except for the last two, which Hecl

automatically passes in. cmd is the command that was

actually called, and shopform is of course the form that the proc was

called with. By comparing $cmd with the various commands that are

available, it's possible to determine which command called the proc, and act accordingly.

Now, let's build it and run it:

java -jar jars/JarHack.jar -hecljar jars/cldc1.1-midp2.0/Hecl.jar \

-destdir ~/ -name ShopList -script shoplist.hcl

/opt/WTK2.5.2/bin/emulator -classpath ShopList.jar Hecl

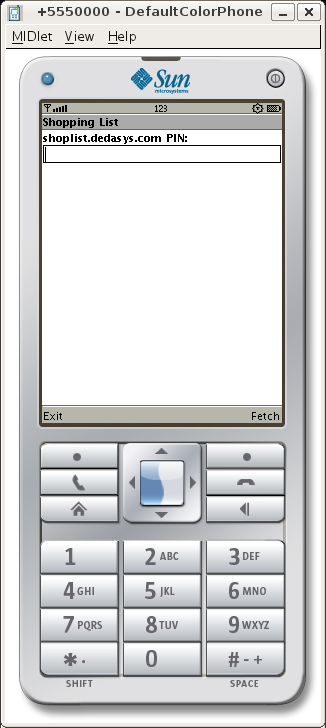

Figure 3: Initial shoplist form

At this point, you enter the PIN number (346764), and press the Fetch

button. This command executes the code in MakeList. The first thing it

does is attempt to fetch the data from the shoplist site, using the

http.geturl command. Since this command returns a hash table, in order to

get at the data returned, I use the hget command to access the "data"

element. If the PIN was not available on the server, an error message is returned, and the

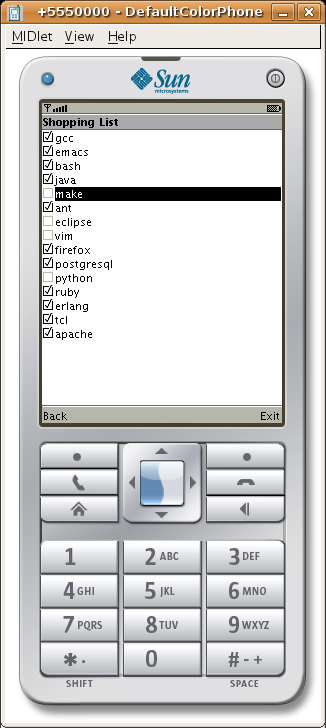

user is returned to the first screen. Otherwise, a list of checkboxes is created with

lcdui.list, by specifying "multiple" as the type. Since the shopping list

is sent "over the wire" (so to speak...) as a list of lines, all I have to do to add it to

the display is split it by lines with the split command, and then iterate

over that list with foreach. The result looks like that displayed figure

4.

Figure 4: Shopping List

And there you have it, a network-based shopping list in less than 100 lines of code. Of course, there is room for improvement. For instance, in the production version of this shopping list application, RecordStore (in Hecl, the rms.* commands make this functionality available) is utilized to save the list and its state between invocations of the program, so that you can leave the application, run it again, and find the list as you left it. Support for multiple lists might also be handy.

Of course, this tutorial barely scratches the surface. Hecl has a number of other GUI commands, and is a complete programming language that can do some interesting and dynamic things. If you're curious, the best way to learn more is to keep reading the documentation, and sign up for the Hecl Google Group, which can be accessed either as a web forum or as a mailing list.